Arthroscopic and Open Tendon Transfers

Tendon transfers are relatively uncommon procedures that can be utilized for either chronic nerve injury or irreparable tendon damage. Utilizing another muscle tendon unit to provide function for a deficient muscle can be very powerful in restoring function, strength and relieving pain in patients with chronic severe injuries. The two primary indications for tendon transfers include permanent nerve injuries (axillary nerve, long thoracic nerve, accessory spinal nerve [cranial nerve XI]) or irreparable tendon damage (rotator cuff - supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis). There are multiple tendon transfers for each of these primary disorders each with advantages and disadvantages. Indications for transfer take into account multiple patient (age, comorbidities, active and passive range of motion) and structural (presence or absence of glenohumeral arthritis, associated tendon or nerve damage). The primary transfers Dr. Tashjian will perform for these injuries include a trapezius transfer (Saha Procedure) or pectoralis major transfer for axillary nerve dysfunction, sternal head of pectoralis major transfer for long thoracic nerve dysfunction, rhomboid major/levator scapulae transfer (Eden-Lange Procedure) for accessory spinal nerve dysfunction, pectoralis major or latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable subscapularis tears and arthroscopic assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer for irreparable supraspinatus or infraspinatus tears.

Dr. Tashjian performs all of these transfers and has an extensive experience performing these relatively uncommon procedures.

Axillary Nerve Palsy

Axillary nerve palsy resulting in deltoid weakness is an uncommon problem. The patient's history is typically associated with either a dislocation of the glenohumeral joint in an older patient, a high energy trauma resulting in a brachial plexus injury or an injury as a result of a shoulder surgery such as a shoulder replacement. Typically, these injuries are identified in both young (brachial plexus injury from trauma) or older (isolated axillary nerve palsy due to dislocation or as a result of shoulder replacement surgery) patients. On physical examination, patients will often have no ability to raise the arm due to weakness of the deltoid. Decreased sensation is often present over the outside portion of the shoulder. Contractures may have resulted secondary to immobility and scar from trauma.

Indications for a muscle transfer for an axillary nerve palsy include patients who have a static injury over 1 year old. Prior to this, nerve transfers (radial nerve) may be considered to avoid tendon transfers. If there is glenohumeral arthritis or severe deformity of the humerus or glenoid, then glenohumeral arthrodesis is considered as opposed to tendon transfer as patients will continue to have pain as a result of the loss of glenohumeral cartilage. In the setting of young patient with good bone quality, a preserved glenohumeral joint with goals of improving elevation to approximately 90 degrees and maintaining rotation (which a fusion would limit), a trapezius transfer (Saha procedure) may be indicated. The acromial process along with a small portion of the clavicle is osteotomized and then fixed to the greater tuberosity of the humerus with several screws. Postoperative patients are in a brace holding the arm at 90 degrees of abduction which is slowly lowered over 3 months as the osteotomy is healing. Therapy is started at 3 months and continued until 12 months postoperative with goals of achieving 90 degrees of active elevation and preserved rotation.

Preoperative AP xray (left) and postoperative axillary xray (middle) and postoperative AP xray (right) after trapezius transfer (Saha procedure) for a chronic axillary nerve palsy.

The alternative tendon transfer for an axillary nerve palsy is a rotational pectoralis major transfer. The entire pectoralis major is detached from the humerus, chest wall and medial portion of the clavicle. The pectoralis is then rotated such that the humeral insertion is inserted posteriorly on the scapular spine and the inferior medial sternal attachment is affixed to the humerus. The pectoralis drapes over the deltoid by tunneling over it. Indications for this transfer include isolated axillary nerve palsy in an elderly patient after dislocation or a postoperative palsy as a result of surgery often a shoulder replacement. Patients are in a brace for 3 months and then progressively working on shoulder range of motion and strengthening for 1 year with expectations to gain 90 degrees of forward elevation.

Long Thoracic Nerve Dysfunction

The long thoracic nerve originates from branches of the upper portion of the brachial plexus directly off the cervical nerve roots. The nerve innervates the serratus anterior which takes origin from the chest wall and inserts on the inside border of the scapula. By history patients will report acute onset dysfunction after a direct blow to the chest wall resulting in winging of the scapula, shoulder pain, weakness in arm elevation and often a limited ability to fully raise the arm. It can also be associated with repetitive overhead activity resulting in scapular winging.

Scapula winging associated with long thoracic nerve palsy

Nonoperative treatment includes rest, NSAIDs and therapy. The nerve after being injured will often take a long time to recover. In general, we will wait atleast 18 months to see if there is recovery. During that time, EMG/NCV is performed to evaluate recovery. If limited recovery occurs, then consideration of split pectoralis major tendon transfer is reasonable. The sternal head of the pectoralis major is detached from the humerus and then routed to the back of the shoulder to be attached directly to the lower pole of the scapula through drill holes. Surgery is outpatient and the patient is in a brace for 6 weeks. Therapy is initiated at 6 weeks for motion with limited lifting up to 10 lbs. At 3 months strengthening is started with 30 lbs of lifting with plan for return to full activity at 6 months postoperative.

Detached sternal head of pectoralis with sutures in preparation prior to transfer (left image) and final repair of the sternal head to the inferior pole of the scapula (right image)

Accessory Spinal Nerve (CN XI) Dysfunction

Cranial nerve XI runs through the posterior triangle of the neck and then dives under the trapezius muscle to innervate the trapezius. Injury to CN XI is typically due to a penetrating injury to the back of the neck or from an injury during a surgical exploration of the posterior neck often due to a lymph node dissection. Patients will have pain and weakness of the shoulder with limited ability for elevation. Typically, patients will have pain along the scapula with significant winging of the outside portion with the scapula rotating around the chest wall.

Lateral scapula winging of CNXI palsy

In these cases, often waiting for recovery is not indicated for surgical treatment as they are due to a direct nerve injury and tendon transfer is warranted. The typical transfer is taking the Rhomboid major, rhomboid minor and levator scapulae and transferring them to the scapula spine (Triple Transfer) as described by Elhassan. Prior to this description, the transfer typically performed is the modified Eden-Lange Procedure with transfer of the rhomboids to the supra and infraspinatus fossa and the levator to the spine of the scapula. Postoperative, patients will be treated very similar to the pectoralis transfer for long thoracic nerve palsy.

Irreparable Subscapularis Rotator Cuff Tendon Tear

The subscapularis tendon is a powerful internal rotator and is critical for function of the shoulder balancing the rotator cuff tendons in the back. Failure of healing after rotator cuff repair can occur as a result of poor quality tissue or age but most commonly subscapularis deficiency occurs as a result of a chronic injury that is neglected or a tear that was not recognized. Severe atrophy of the muscle with retraction of the tendon past the glenoid or cup of the glenohumeral joint will often be considered unfixable or irreparable. Patients will often complain of weakness of rotation towards the belly and even weakness in elevation. MRI will show near complete atrophy of the subscapularis muscle and tendon retraction to the glenoid.

Atrophy of the subscapularis muscle associated with an irreparable subscapularis tear

Treatment for irreparable tears include reverse shoulder arthroplasty or tendon transfer. In patients with an intact posterosuperior rotator cuff and no significant arthritis, tendon transfer is a reasonable alternative.

The two options for tendon transfer include the transfer of the pectoralis major and the latissimus dorsi tendon. Both are reasonable options with comparable data to restore internal rotation strength and function. Pectoralis transfer will often lead to slightly more cosmetic deformity but there is more clinical data supporting its use over latissimus dorsi. Biomechanically the latissimus has better theoretical advantage of improved strength compared the pectoralis.

Released pectoralis major tendon prior to repair (left image) and after transfer (right image)

Released latissimus dorsi tendon prior to repair (left image) and after transfer (right image)

Postoperative patients will go home the same day and are in a sling for 6 weeks. Home based stretching occurs during the first 6 weeks. At 6 weeks, the sling is discarded, and formal physical therapy is started. At 3 months, 20 lbs of lifting is allowed and strengthening is pursued. At 6 months patients return to full activity. Significant improvements in internal rotation strength and shoulder function will occur with either transfer.

Chronic Irreparable Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus Rotator Cuff Tears

The most common transfer performed is for chronic irreparable rotator cuff tears either after a failed repair or in the setting of no surgery. Typical indication is a younger and often male patient between 40 and 65 with a chronic irreparable supraspinatus and infraspinatus tear with weakness in elevation and pain. Patients can have the complete inability to raise the arm as this is not a contraindication. The patients require some preservation of the space between the humeral head and the acromion process of the scapula and need to have no arthritis or at most mild arthritis of the glenohumeral joint. Older patients or those with no joint space or articulation of the humeral head to the undersurface of the acromion require a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

In the properly indicated patient, an arthroscopic assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer is indication. The lower trapezius is harvested off the scapula and then elongated with an Achilles tendon allograft. The allograft is tunneled under the deltoid and then arthroscopically fixed to the humerus at the insertion site of the rotator cuff. The benefits of this transfer are that the lower trapezius pull is in line with the rotator cuff in the back therefore it is easy to replicate. Arthroscopic transfer allows small incisions and a lower risk for nerve injury or infection.

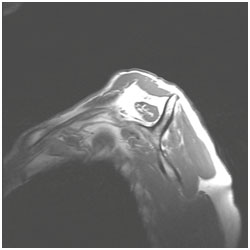

MRI with atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus in an irreparable tear

Lower trapezius tendon after harvesting (left side of left image) and after extension using Achilles allograft tendon (middle image) and final arthroscopic image of the repair of the allograft to the supraspinatus footprint of the proximal humerus (right image)

Lower trapezius transfer is outpatient. Patients are in a brace for 6 weeks followed by a sling for 4 weeks. Physical therapy starts at 6 weeks postoperative. At 3 months 10 - 20 lbs is allowed and strengthening is started. Return to full activity is allowed at 6 months postoperative. Functionally patients have significant improvements in strength and shoulder function as well as pain relief often allowing return to sport and manual labor.